Breaking: Biden’s Bureau of Indian Affairs Boondoggle: Wisconsin Residents Stranded amid Tribal Dispute

- Obtenir le lien

- X

- Autres applications

Lac du Flambeau, Wis. — Imagine waking up for work, pulling out of your driveway, and then coming to the end of your block to find the road closed by, say, the French government. When you ask why, the gendarme informs you that between the American road before you and your equally American driveway behind you is a patch of French territory. Because of a dispute with the township, the local French consulate has decided to bar the road until such a time as it deems fit. The mayor and the governor are powerless, as this is a foreign-diplomatic matter — the legal province of the federal government. How ridiculous!

That's close to what has happened in northern Wisconsin — the Lac du Flambeau tribe has blocked small but vital sections of the roads, making it impossible for non–Lac du Flambeau tribal residents to access public throughways. Beginning on January 30, restricted access to the wider world has been an aspect of normal life for dozens of families.

"When you look at the larger area of the tribe of the reservation, there’s roads like this all over the place that squirt on and off tribal lands," says Dave Miess, a local landowner. "It’s just the way it’s set up. We’re kind of wondering, are we just the first low-hanging fruit [for such pressure campaigns against the federal government]?"

Simply put, the tribe wants money in exchange for allowing nonmembers to access their patches of road, and the bill hasn't been paid in ten years. The conflict came about and has been sustained by deeply contradictory resolution structures. Local problems between the tribe and non-tribal landowners are made a federal concern, and the process for legal resolution is expected to begin in the lowest courts and then travel upwards — in a matter of months and years.

The tribes are ultimately the wards of the U.S. government, which has established the Bureau of Indian Affairs to preside over the Indian nations. This arrangement is an amalgam of centuries of federal policy regarding the tribes. It comprises constitutional provisions (interstate-commerce clause), treaties, and congressional legislation that has undergirded this intractable situation and maintained it for the past 140 years.

Maybe most important to understanding the Lac du Flambeau problem is the Dawes Act of 1887, legislation that was sold as an effort to incorporate the tribes into the broader American experiment by atomizing tribal land ownership — giving individual families ownership of what was shared land to do with as they wished, including the selling of said land to non-Indian individuals. When these policies were found wanting (for all sorts of granular reasons that I will write about at length in a magazine piece), the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 re-established the tribal lands as shared land but required the grandfathering of land sales that had taken place over the previous 47 years. In other words, tribal lands were dotted with little duchies of non-Indian land.

Since these duchy landowners needed access to their properties (effectively, outposts of the U.S. within the quasi-independent tribal lands), they made right-of-way access and easement agreements with individual locals outside of the tribes. Most of the time, these agreements — representing economically and culturally dissimilar neighbors making peace — work well enough to avoid national press attention.

The issue in Lac du Flambeau is that access agreements, and payments, have not been observed for ten years, and many current homeowners have unknowingly purchased homes that have these outstanding legal issues.

Frustrated by inaction and a lengthening bill because of it, the LDF tribe erected barriers around the patches of road they own that neatly snip public road access to some 60 properties owned by non-tribal landowners. With a few plywood barriers, cement cubes, and a length of chain, the tribe turned the tables on the landowners and their title companies.

The governor, senators, congressmen, and various officials have tried to mediate, but the tribe is refusing to come to the table. As a result, homeowners have been forced to walk across frozen lakes and through woods to neighbors' homes that aren't cut off by tribal jurisdiction and park their cars at these other properties. Non-tribal residents are permitted to access the blocked roads only for medical issues. An autistic kid was not allowed permission to pass through to attend school, meaning that he and his mother had to live with family elsewhere. One couple, who work an hour away, take their snowmobiles across the lake to their car, where they then commute to work — a rather perverse multistage rally biathlon.

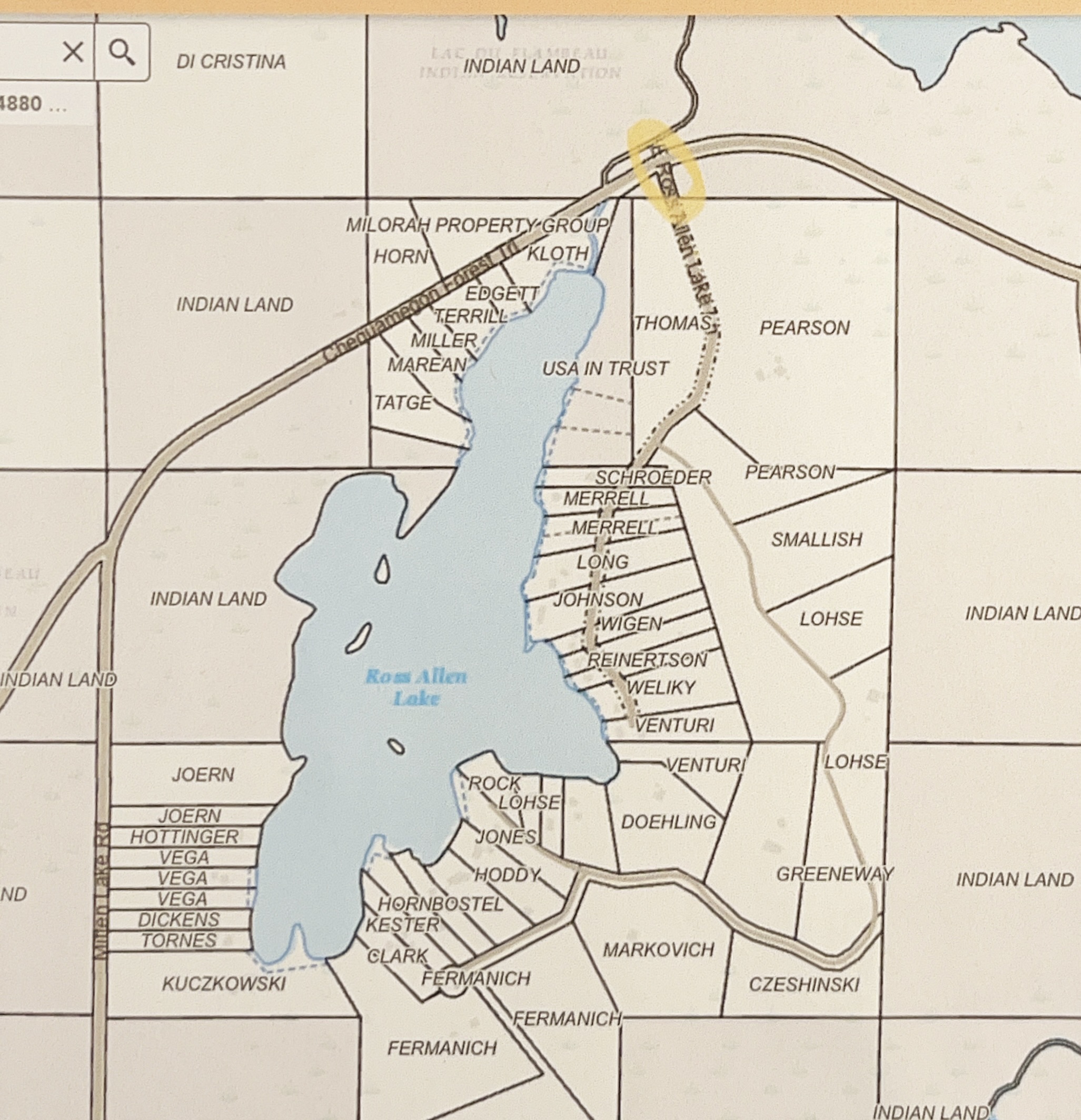

When I met Miess at a local Caribou Coffee, he brought along maps depicting the couple of hundred feet of tribal land that suffices to cut off access to public roads. The tribe is asking for $20 million, while the title companies and a past BIA note thought a figure under $100,000 would be appropriate. Since the roads closed, however, the BIA has said and done nothing.

All letters to the agency, such as those from Senator Tammy Baldwin and district representative Tom Tiffany, have gone unanswered. Senator Ron Johnson's office did not respond to a National Review comment request about his views on the matter, and neither did the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council CEO and the Lac du Flambeau Tribal Court.

As I spoke with Miess, who has now gone a full month of abridged access to the wider world, he reiterated what he's said in past interviews, that he understands the tribe's frustrations, but that it's hard for him to be too sympathetic when their silence and noncooperation is prolonging the discovery of an acceptable resolution. Most frustrating of all, the one agency that can force the end of this standoff refuses to act or speak.

"[We're] very, very, very worried," adds Miess. "For one, our house is worth nothing. Right? . . . We’re all thinking what happens when the lake melts. Well, we have boats, but we're relying on the continued good graces of our neighbors across the lake."

The Bureau of Indian Affairs has the authority, granted it by Congress, to make the ten-year dispute end — this makes it a failure starting under Obama and continuing during the Trump administration and now, most palpably, the Biden administration (the grayer version of the Obama administration). As described to me by John Tahsuda, former principal deputy assistant secretary of Indian Affairs, this issue should have been relayed to D.C. by the regional office years ago:

I don’t say this in a bad way. But I really feel like that’s a leadership responsibility to let the people below you know: Don’t be afraid to bring a problem to me. Or [expect that employees will] give me a heads-up. Sometimes the message that gets passed down is "I don’t want to hear about it."

What was a matter of money is now one of public safety, as Americans cannot access food, medicine, and the repair of their homes without a foreign government's police force granting them access and collecting their trash. What was sufferable during winter — as the residents, almost all of whom are of retirement age, trekked down ice-covered hills and across a frozen lake pulling their groceries in sleds — will become impossible as the thaw arrives. Then, they'll have to pick their way through the woods; already, some have experienced falls. These are older Americans whose homes are now worthless, who have been abandoned by their government because the Biden administration is unwilling to force a tribe to the negotiating table.

I don't blame the tribe as some do. This is a desperate gambit to force the federal government — no friend of tribal rights — to make a decision. The tribe has waited ten years for the BIA. By weaponizing the same bureaucratic sclerosis that has foiled the tribe's attempts to get what it is due, it has made national news. If it weren't for the Biden administration's seemingly bottomless ineptitude, the tribe would have restitution by now. However, the tribe is risking high stakes. Its gambit can go sideways just as soon as a non-tribal resident suffers a serious fall because the blocked roads have forced him to stumble through the woods.

Biden, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland need to resolve this as soon as possible.

|

- Obtenir le lien

- X

- Autres applications

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire

Thank you to leave a comment on my site